An American entrepreneur best known as the co-founder and long-time executive of Calvin Klein Inc.However, Barry Schwartz’s true passion was, and still is, horse racing. He is an owner and breeder of thoroughbred horses, a member of the Jockey Club, and has repeatedly won awards in the world of racing. Schwartz is also a collector of stamps and a philanthropist who supports cultural and educational initiatives. Read on bronx1.one to find out how he managed to bridge the worlds of high fashion and horses.

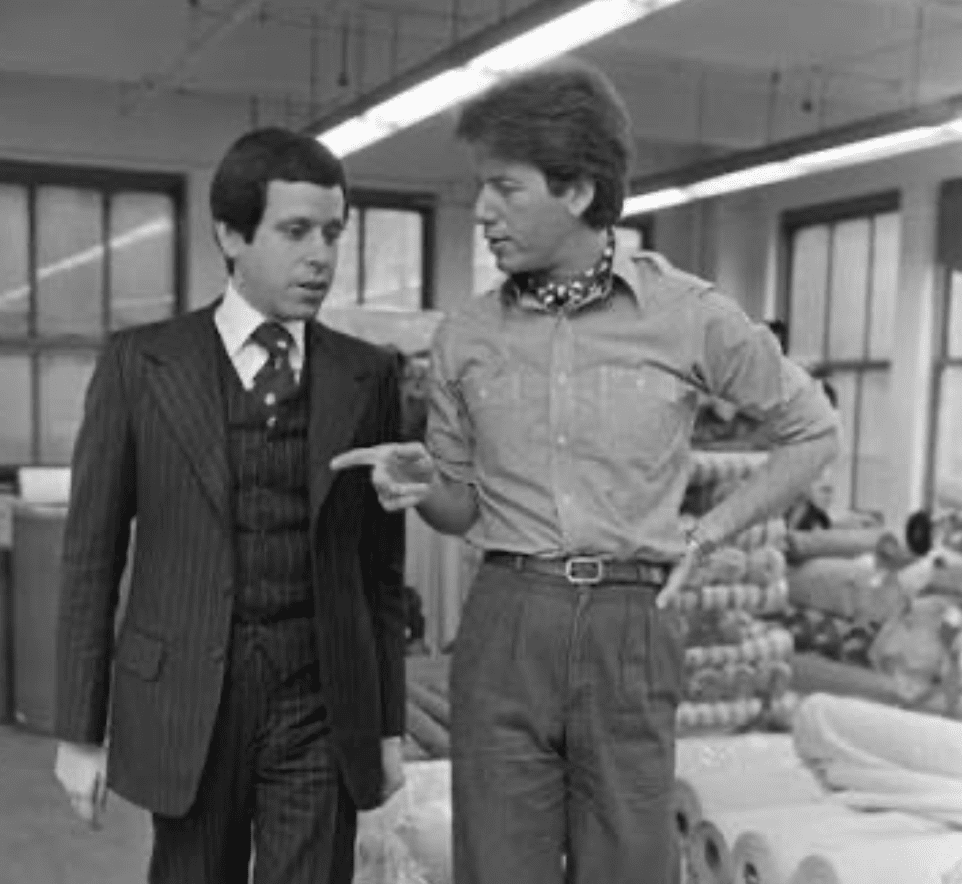

The Shadow Architect of Calvin Klein

Barry Schwartz was born and raised in humble circumstances—his childhood was spent in a one-room apartment in the Bronx. Life was tough. When Barry turned 21, he lost his father, who worked as a grocer. Yet, it was this experience that forged his entrepreneurial character.

As high school students, he and his childhood friend Calvin Klein—both sons of small grocery market owners in Harlem—started earning their own money. The boys would buy newspapers for five cents and resell them for double the price in hotels. Sometimes they brought home three dollars a night, which was a small fortune for teenagers at the time. This is where their partnership began: Schwartz—the rational and practical one, and Klein—the creative and ambitious one.

In 1968, Schwartz took on the role of financier, investing $10,000 in a joint project with Klein, Calvin Klein Inc.Their first office in a New York hotel was far from luxurious. It was Room 613, with a door that opened directly onto the elevator. Hanging inside were only six coats Klein had sewn with Schwartz’s money. And it was a stroke of luck that brought them their first big break.

One morning, Don O’Brien, the head of the prestigious Bonwit Teller department store, stepped off the elevator. Upon seeing the coats, he was immediately interested. A few days later, Schwartz got a call from an excited Klein:

“You won’t believe it—we got a $50,000 order!”

That was the beginning of the brand’s rapid ascent. For decades, their partnership worked flawlessly. Klein created; Schwartz calculated and built the system. He is often called the “shadow architect of Calvin Klein” because without his cold logic and managerial talent, the brand would hardly have become one of the most influential in the fashion world.

In 2003, when Calvin Klein Inc. was sold to Phillips-Van Heusen Corporation, Schwartz stepped back from active business. But his name remains forever etched in the history of the fashion industry as a symbol that behind every brilliant designer stands a shrewd strategist.

Camelot at New York’s Racetracks

Barry Schwartz was passionate about horse racing from childhood. His dream came to life in 1978 when, thanks to his acquaintance with Carl Rosen, the owner of the legendary filly Chris Evert, he bought his first thoroughbred. Schwartz soon established his own farm, Stonewall Farm, in Granite Springs, which became a true champion factory.

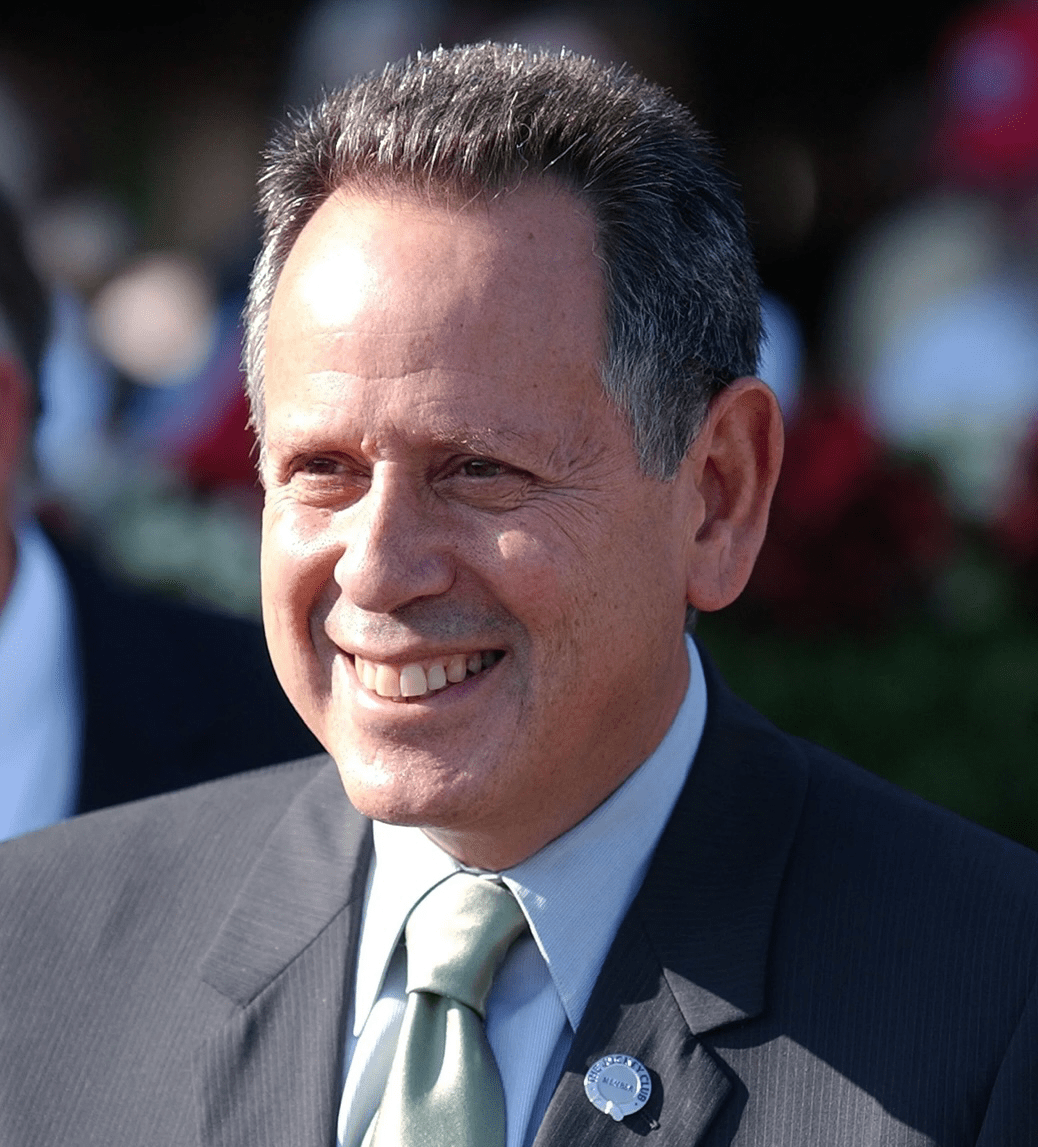

Despite his career in the world of fashion, he never abandoned his love for racing. In 1994, he was elected to the board of trustees of the New York Racing Association (NYRA), and in the fall of 2000, at the insistence of industry legends Kenny Noe and Dinny Phipps, he became its Chairman and CEO. What is particularly striking is that Barry performed this job while simultaneously running Calvin Klein Inc. Every morning, Schwartz drove through rush-hour traffic to be present at both locations. He genuinely believed that New York should have the best horse racing in the world.

His first two years at NYRA were like a honeymoon.

Schwartz opened the organization’s doors to fans and bettors—the people who supported the sport daily with their wagers. He launched a new website and asked fans:

“What should we change?”

More than four thousand responses were translated into concrete actions: standardized saddle pads for spectator clarity, public announcements of claims to buy horses after races, and an information board for horseshoes. For the first time, fans felt their voices mattered.

“Without the fans, there is no sport,” Schwartz often said.

His approach was called a seismic shift; he turned racing back toward the people who sustained it. Regular NYRA employees also felt the changes under Schwartz’s leadership. By returning overpaid taxes, he gave everyone a 5% raise and Christmas bonuses—an unprecedented event for the association. The atmosphere changed, and the racetracks at Belmont Park, Saratoga, and Aqueduct were filled with a sense of fairness and new energy.

“It was Camelot,” people later recalled. “A short but brilliant era”.

His final two years in office proved difficult; the battles with politicians and bureaucracy were draining. Schwartz eventually left NYRA in 2004, frustrated by the collapse of what he was building. But even those who didn’t always agree with his decisions acknowledge that Barry Schwartz’s time was special. He proved that racing could be honest, transparent, and inspiring.

Interesting Stories from NYRA

Barry Schwartz’s four years of leadership at NYRA left behind many emotional and memorable moments. Here are some of them.

The Cup After the Tragedy

On the morning the planes struck the Twin Towers, Schwartz was at home in New Rochelle. He watched the events in horror. Yet, the responsibility fell to him to decide whether the planned international tournament would proceed. Belmont Park was only 12 miles from “Ground Zero,” and no one was sure if they dared to hold the event. Schwartz, like his ally Dinny Phipps, insisted: New York must show that it is alive and strong.

On October 27, the racetrack welcomed guests under unprecedented security measures: armed snipers on the roofs, police, and FBI agents on the grounds. Despite everything, a sunny day, a parade of jockeys with flags of different nations, and an American winner transformed those races into a true symbol of revival.

The Pick Six Scandal

The following year, NYRA had to overcome another crisis. In 2002, three students from a college fraternity attempted to cheat the betting system, presenting six identical winning Pick Six tickets worth over $3 million. Thanks to the vigilance of the organizers, the conspiracy was uncovered before payment. Had the scammers received the money, it would have been a disaster for racing’s image.

Defending José Santos

Another high-profile story unfolded in 2003. After jockey José Santos won the Kentucky Derby, the Miami Herald accused him of cheating. Journalists insisted he had supposedly used an electronic device (a buzzer) to win, based only on a telephone interview with the jockey (where his English was imperfect) and a single photograph that looked suspicious to the reporters. Schwartz immediately stepped in to defend the athlete, enlarged the photograph, and proved it was just a visual illusion. It was actually a piece of silk from the uniform of another jockey, Jerry Bailey, riding behind him. Thanks to NYRA’s decisive action, Santos’s name was fully cleared.

Revolutionary Decisions

But Schwartz’s true legacy at NYRA lies in economic changes. He was the first in the industry to apply the simple business logic he used at Calvin Klein: if the product isn’t selling, lower the price. He pushed for a reduction in the “takeout” percentage from bets, which immediately increased fan interest and prize money. The results were clear: attendance and overall wagering grew at record rates, and NYRA became an example for the entire country.

Schwartz viewed horse racing as a retail business and always sided with the fans. It was thanks to him that New York experienced a true “Golden Age of Racing” in the early 2000s, which fans still remember.

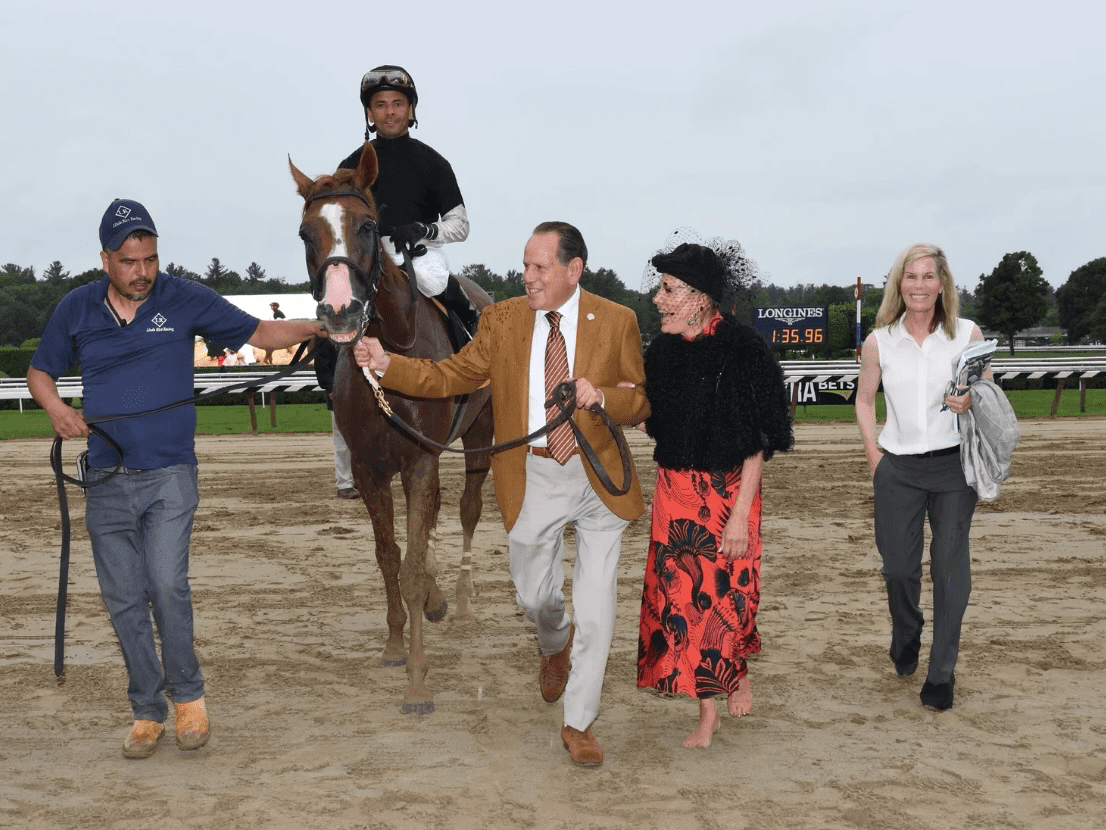

The Two Passions of Barry Schwartz’s Life

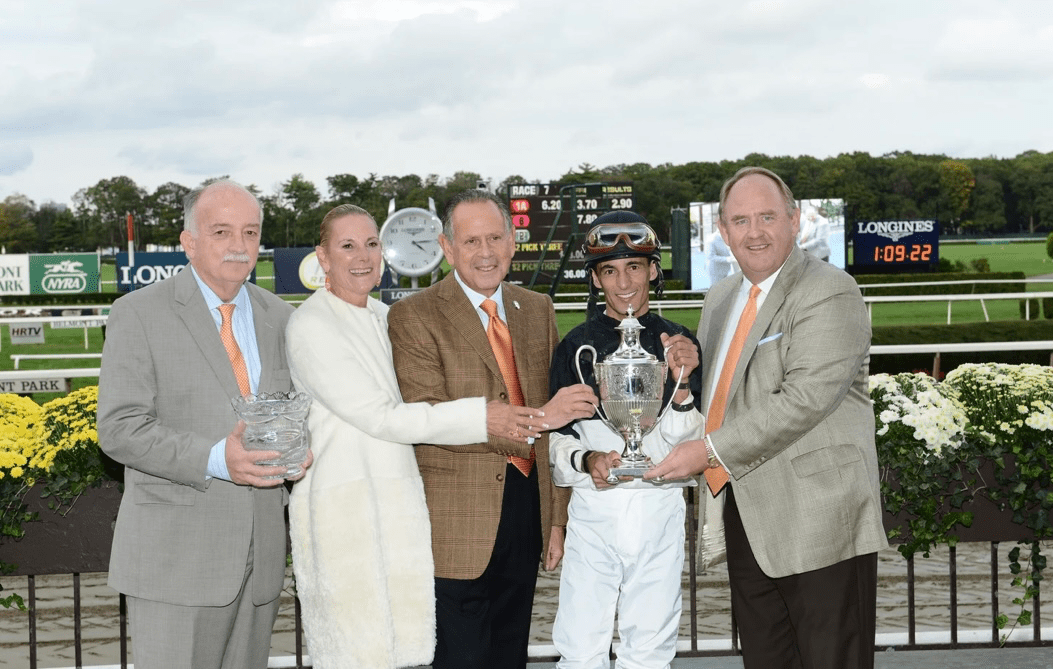

Barry Schwartz always divided his heart between two passions—his wife and horse racing. He remained a dedicated owner and breeder of thoroughbred horses for nearly 35 years. His horses’ names repeatedly appeared on stakes race winner lists: Great Intentions, The Lumber Guy, Princess Violet, Perfect Poppy, Seeking the Sky, Fire King, Turnofthecentury, and the legendary Three Ring. In 2001, Schwartz was honored with the Alfred Vanderbilt Award for the person who made the greatest contribution to the development of racing.

Barry Schwartz bred 26 horses that earned over $200,000 each. Among the most successful were Boom Towner, Voodoo Song, Kid Cruz, The Lumber Guy, Princess Violet, Three Ring, and Fire King, whose wins brought in between $700,000 and a million dollars.

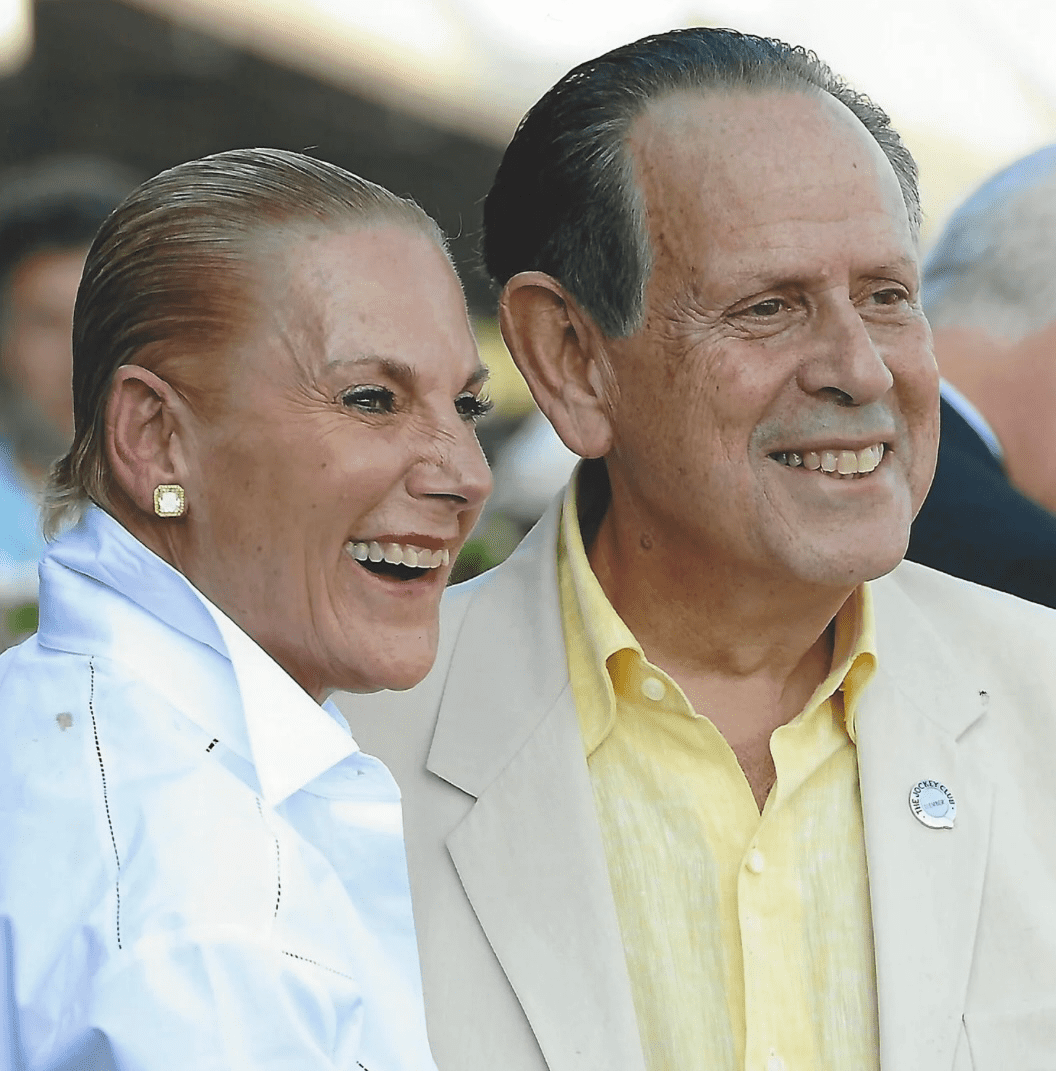

Today, Barry and his wife Sheryl, whom he met in 1967 on a blind date at Roosevelt Raceway, live on their 700-acre Stonewall Farm in northern Westchester. The couple also has a second home in Santa Barbara, where they spend time near the ocean. They have two children. Schwartz manages investments, runs the stable, and actively supports educational and cultural initiatives.

Besides horses, Schwartz has another hobby: philately. He is a board member of the Philatelic Foundation of New York and views stamp collecting as a way to combine history, aesthetics, and intellectual challenge.

Barry Schwartz’s life is an example of how a businessman who built a global corporation managed to stay true to his childhood dreams and turn them into a second career.